First of all, sorry it has been over a month since I've posted. I've decided to get together a few people to start addressing some of the things I write about, and that has taken my time up til now. I'll be posting once per month from here on out, on the first Sunday of every month. Today's post is a long one, but one of the most interesting I've written by far.

This is the one time where I will say the following: if you are short of time, skip directly to the math section. It shows a serious glaring deficiency of either forethought or disclosure on the part of the founders of Solar Roadways. Moreover, it shows they can't do basic math. Never trust an engineer who can't do basic math. It's a very crackpot idea.

Here We Go!

I've heard a lot of talk about Solar Roadways recently. I'm going to use it as an example of how to analyze some "science." After you follow the very basic math below, you will see that the team at Solar Roadways does not know what numbers to run*. A much larger problem: they suggest that solar roads can replace fossil fuel power, while simultaneously and surreptitiously admitting that they need a ton of grid power to make this work. So pretty much they are either dumb or straight up liars.

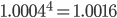

First, let's talk about why these roads might be good, from their point of view. Being a by-the-numbers type of guy, the first thing I did was check the "numbers" section of their website. While their assumptions are dubious at best (more on that later) They say that their roads could provide 3x the energy that the US needs, in kilowatt hours (kWh is a useless measurement here, cause it will be intermittent power. In other words, it produces no energy at night, and will need to be supplemented by fossil fuel power. More on that later). Also, the roads look a lot cooler, with light-up sections, and ability to melt snow so that road maintenance is reduced.

So the thing is wired to the grid so that if it snows, it can use heating elements to melt the snow instead of plowing it. But doesn't snow take a lot of energy to melt? Would it take less energy just to push it with a plow? Time for the math!

Math of Melting vs Pushing Snow

Okay. Let's assume middle-case scenario of 8 inches of snowfall, being removed with one sweep by plow trucks, and that this is between powder and heavy snow in consistency, which means 1" of water equivalent. A DOT snowplow clears 10' width of snow, or 120 inches. In one foot of movement forward and plowing 8" of snow it moves the water-weight of 1"x120"x12" or

Now we have to figure out how much energy cost this took in fuel, so we will later relate this to the mileage efficiency of a DOT truck. First, let's figure out how much energy it takes to melt this much snow into water. Do do this we need the latent heat of fusion, or the energy it takes to transition from ice to snow. It's 334 Joules/gram. How do we convert from cubic inches of water to grams? Easy. Because the metric system makes sense, one  of water = 1 gram. There are 2.54 cm per inch, so:

of water = 1 gram. There are 2.54 cm per inch, so:

Okay, we have grams, now let's calculate the energy to melt as much snow as a plow moves from driving 1':

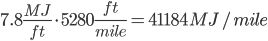

Or ~7.8MJ. Per foot. Or, for a mile:

to melt 8 inches of snow.

to melt 8 inches of snow.

Okay, so, a plowtruck uses diesel. Each gallon of diesel has 136.6MJ. Very conservatively assuming a plowtruck gets ~5 miles to a gallon (I'm guessing it's more like 10, someone who has driven one, correct me and I will correct these #'s), it would take 27.3 MJ to plow one mile of snow. Compared to 41,184MJ to melt it. It literally takes 1500x as much energy to melt is as it would to move it.

This is what you would call a very very bad idea. Engineers as cofounders should know better than to let this slide as a potential solution.

End of Math Section

Okay, so now that we've completely dismantled the case of using these things to melt snow, lets move on to some other issues. We'll skip the minor issues, because that's just nitpicking, and move straight to the parts where they just don't know what they are talking about, and finish with things they clearly know about, but are purposefully misleading people with in order to get more money. Finally, we will close with me realizing that Nathan Fillion is a fool.

Okay, to the problems with this solar roadways project:

Dubious assumptions:

Things they don't understand: the supply lines of a very basic input.

REE mining in China is not a clean thing. Nor was it great in the US. Right now there is not enough world production to make enough of these solar roadway tiles. Look at this article to see more pictures of REE production in China.

They assume an 18.5% efficiency of the solar panels. These are panels that use Rare Earth Elements (REEs). On their FAQ, when someone asks if they are using REEs, they state (paraphrased), "Our electronics don't use silver or gold" (neither of which are REEs, so they are either changing the topic or don't know what question they are answering) "but we can use any solar cell." Good that they can use any solar cell, because there is not enough REE production in the world to produce solar at the scale they need to even replace one major highway with these. Bad they they use 18.5% as their assumed efficiency, because solar cells in this range of efficiency use REEs.

REEs are pretty much only produced in China, because producing them make a massive amount of pollution. Decades ago every other major country quit producing REEs because of the pollution they cause, and because China didn't care about pollution or health hazards, so the world was happy to let them pollute themselves and take their REEs. It's been so long since the US produced REEs that we literally don't know how. Solar Roadway's answer is "let's leave this to the government." They aren't addressing the problem at all. While other countries are looking to have their own production, it will take a very long time for this to come to fruition, and the production rate still won't be enough for a second-rate harvesting design (flat roads with bad optics vs. tilted panels with great optics to concentrate light perfectly).

At best, they can go with non-REE solar cells, which have about an 5-10% efficiency. That means that each of their hexagonal panels will produce half the power anticipated, and thus will make half as much money toward recuperating their costs. In other words, these non-REE solar panels need more basic raw materials (in terms of roadway) per kwh produced, and thus will cost more per unit energy, in an already material-intensive design for a solar cell. This shows that the project is lacking in any real expertise or understanding of the core problem they are trying to solve. Keep in mind that these are not dealbreakers. The team could hire an expert, or consulting, to fill in their knowledge gaps (likely the former, consultants are expensive, and they really need long-term help to bring this to fruition). Also, it doesn't negate all the other benefits of the solar roadways. Finally, non-REE solar panels are a hot topic in research. If the rest of the solar roadways tech is developed, and they are just waiting for good solar cells, it will rapidly enhance future deployment.

In short, the solar cells are a slight additional benefit to whatever holds them in this case of mass-distribution and inefficient use of cells. So if this new road itself doesn't compare favorably to asphalt, the project is sunk in the water.

Things they are just completely wrong/misleading about: melting snow, shutdown of fossil fuel, price of energy

We discussed the melting of snow. They suggest it replace snowplows. Bad idea. It's clearly not going to work, energetically speaking.

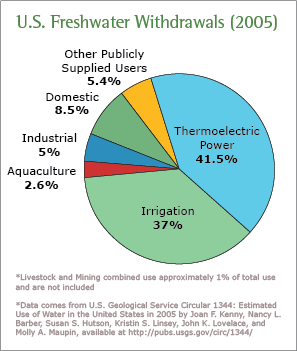

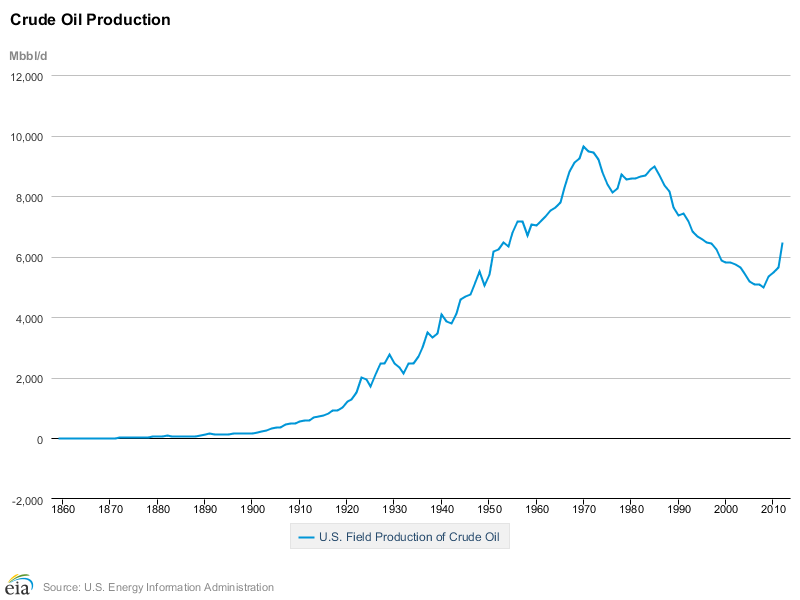

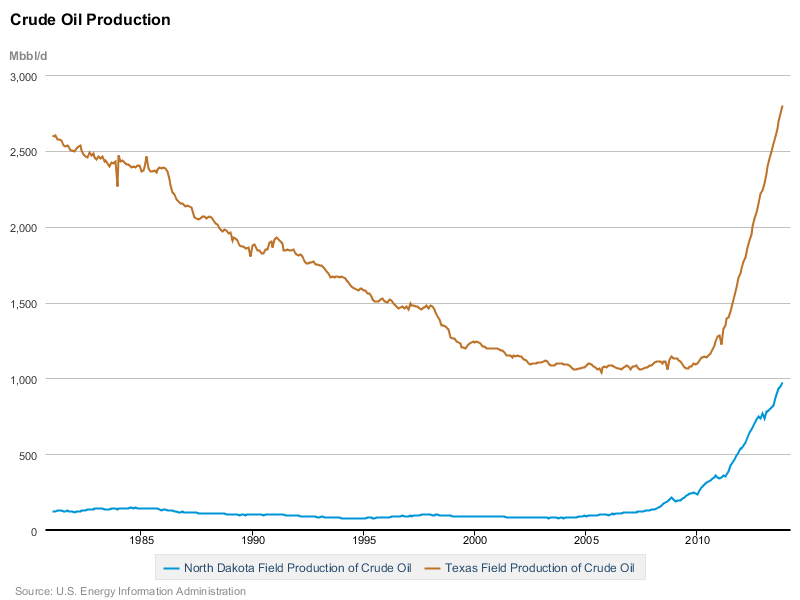

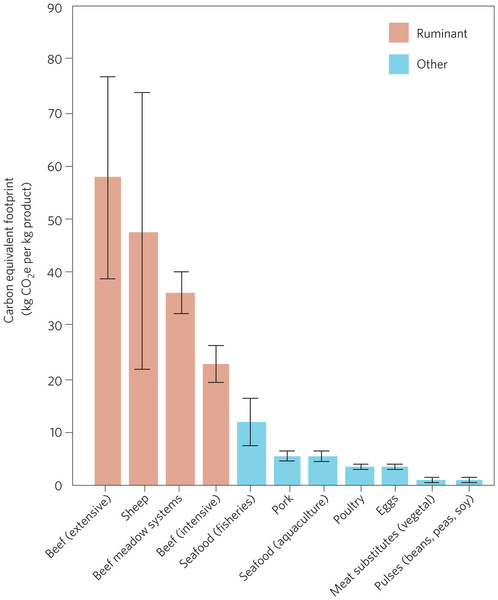

They keep talking about how 50% of US electricity use is from fossil fuels, and how these roads are going to replace it. This is so wrong that it is hard to debunk in one post. But here goes: First, only 40% of US primary energy (my link, please read it for background if you feel a bit lost, it is far briefer than this post) is for electricity. Second, only 66% electricity of this comes from fossil fuels. In other words, 26.4% of US electricity comes from fossil fuels (if we change all our transportation over to electric, these numbers will change, but that would require these roads to have induction power installed - AKA roads that provide the car with energy for driving so they don't have range issues). This is the total amount of emissions that could be replaced by solar roads in their current design.

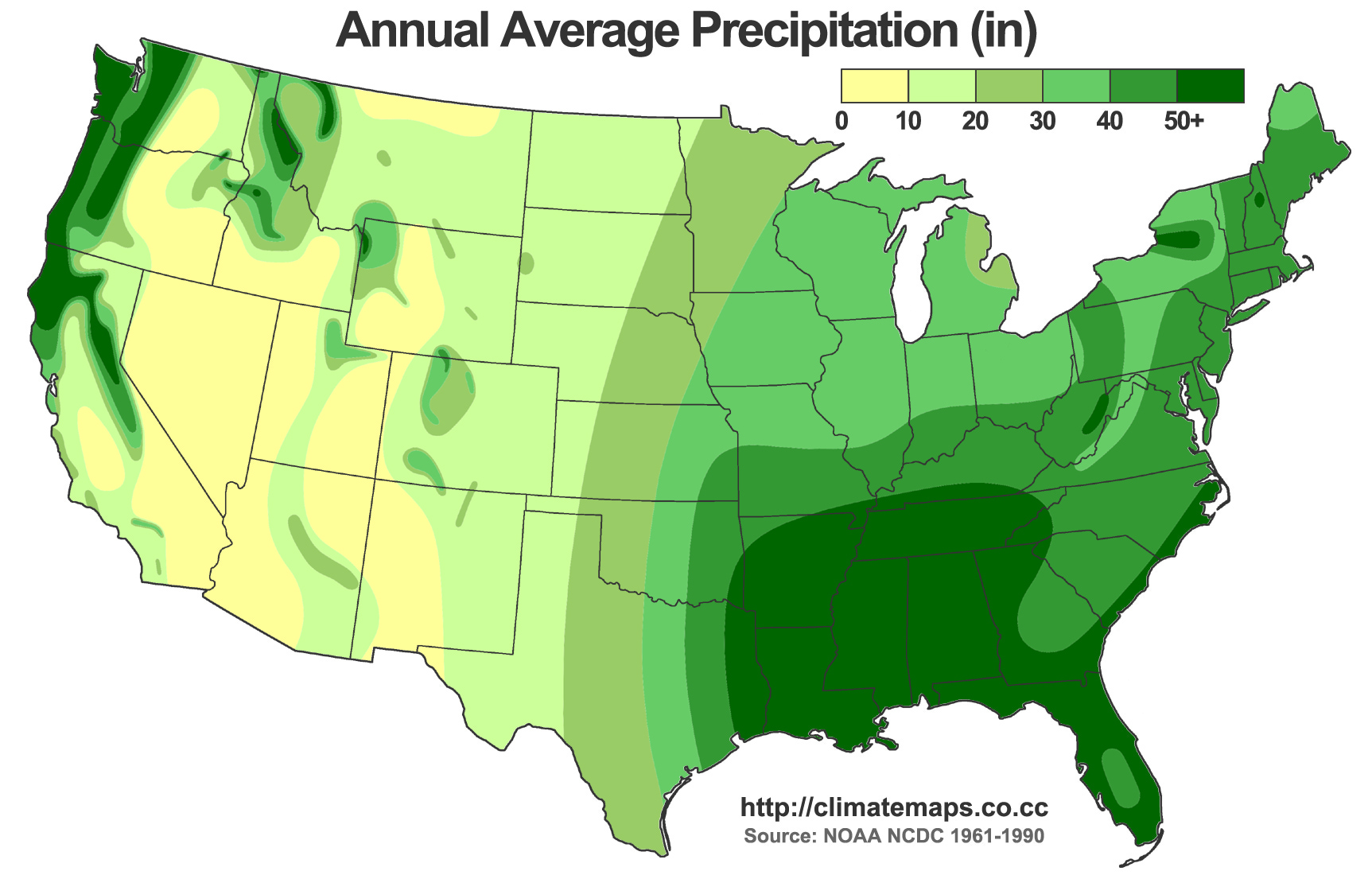

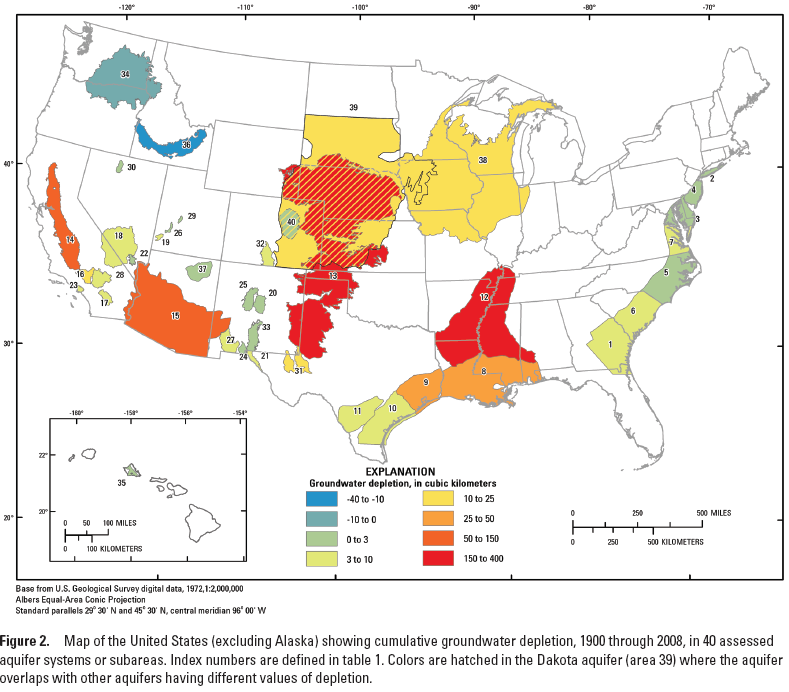

Primary energy in the US. As detailed by the math above, only 25% of primary energy in the US can currently be replaced.

So, pretty much they are off to a bad/misleading start there. But this is nitpicking. The real issue comes in when they talk about replacing fossil fuels. First, they talk about heating the roads. This means they will have to put energy into the roads. Where will this energy come from? Power plants. So much for shutting down fossil fuel. But wait, there's more! Solar power is intermittent. It doesn't even work at night, so power plants also have to be on then. So pretty much, their idea of shutting down power plants is completely shot out of the water by these two things. Can solar roadways still be part of a larger energy solution? Well, not if they are heating roads to melt snow. That just takes far too much energy. If they scrap the melting snow idea and go to just producing energy? Yeah, it might help some. But let's get to one last funny part, the one that shows they know that they won't be shutting down fossil fuel power any time soon.

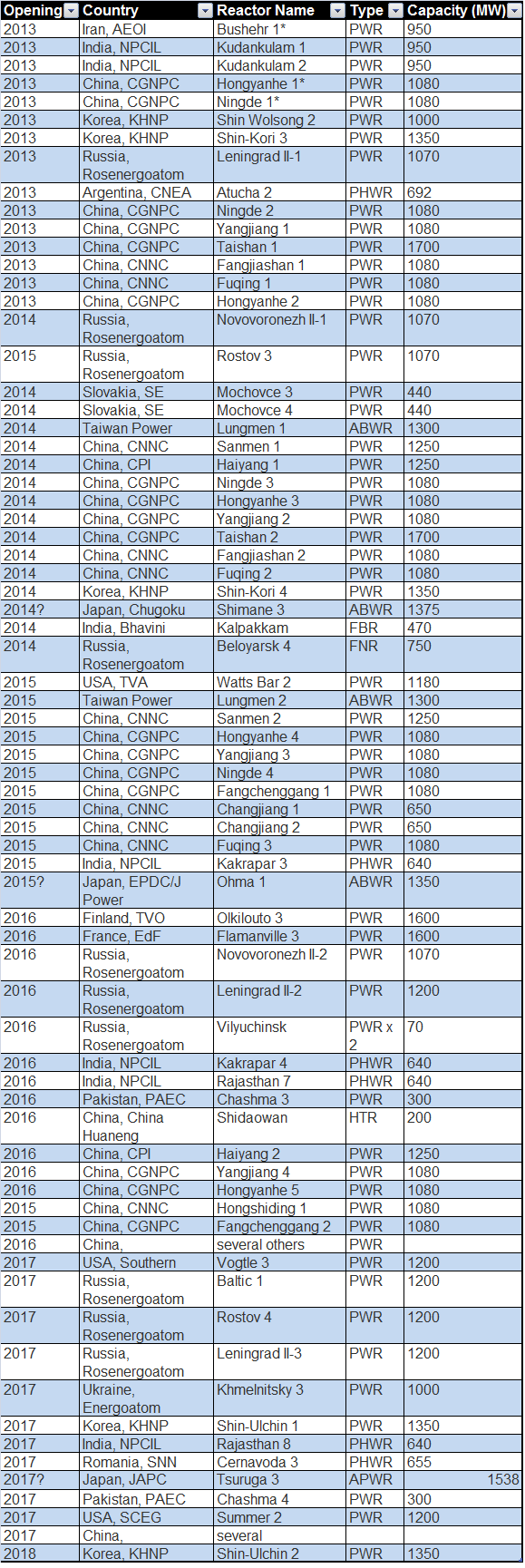

Energy storage. From their FAQ, they mention that there will be "virtual storage" in that during the day they will add power to the grid, and at night they will take power from the grid. This is double-speak to mean: during the day we will provide power that can offset coal and natural gas power plants. At night when we aren't producing, natural gas powerplants (again, my link) will fire up to power our roads (nuclear is not an option for power phasing like this, nuclear powerplants don't spin up or wind down on half-day timescales). In other words, they fully well understand that they aren't going to do away with the rest of the power grid, and that they aren't going to replace all those fossil fuel emissions. So pretty much, saying that these can replace our power grid is double-speak sales points.

The final problem? They don't understand energy distribution. Electricity is produced at about $0.03 to $0.08 per kwh at a power plant. By the time it arrives to us, we pay $0.13 to $0.25 (or $0.50 in Hawaii), because distribution costs a lot of money. Solar panels on our roofs produce power that costs about $0.15 to $0.20 cents per kwh, give or take. So the end-user cost of grid power is the same as that of house solar. But if you run that solar power through the distribution channels and add that price, suddenly you're talking $0.25 to $0.40 power. So, unless they are giving this power away for free, it's probably not gonna be a great solution.

Some Solutions

I've softened my usual tone quite a bit for this writeup, cause I don't want to be a complete naysayer of something who is trying to do something positive (sorry, I know how much you all know and love my biting sarcasm and scathing reviews).Outside of their false solution of trying to solve the energy/climate issue, this idea has some potential. On that note, rather than pointing out problems, I've come up with some great solutions.

My suggestions:

1: Nix the whole melting of snow concept to replace plow trucks. Energetically, it doesn't work. Plow trucks should still exist. Instead of replacing them, replace the salt and sand they need to spread. Make it so plowtrucks plow all but the last 1/8" of snow, then melt that (note, this is still a tremendous amount of energy, but stay with me). This will have a few benefits:

- No more salt and sand on roads means less salt and sand damage to vehicles, making vehicles last longer

- No more salt and sand on roads means that DOTs can save money buy not buying these things

- ... no salt and sand runoff, which pollutes local waterways

- ... animals that go to roadways in the spring to lick off accumulated salt won't do that, reducing traffic accidents from moose and deer, etc.

2: Get a bit more cognizant or REEs and their limitations. Don't use bad assumptions that are easy to poke holes in.

3: Stop selling people on false promises of doing away with fossil fuels. It makes the whole green movement look bad when prominent people are lying or severely misinformed.

4: Focus on the real potential of making these have inductive energy for electric cars. This could eliminate range anxiety (people fearing their electric cars will run out of energy and leave them stranded). Electric car sales will move a lot faster if people can drive from LA to SF, or between Boston/NYC/DC. The potential partnerships include every major car company that markets in the US. Also, this could reduce oil use, and drastically reduce air pollution from cars in these busy areas by further replacing combustion engines with electric ones (even if we power them with electricity from coal, a well-scrubbed coal plant produces fewer bad things than a car). Moreover, since people won't need fuel, they could be assessed a charge per mile driven instead. By whoever owns the roads. Here is your real money-maker for the roads, fellas. It will be far more lucrative than producing tiny amounts of electricity. Please get on this. It will lead to more electric car research, and more rapidly drive forward battery development, and it turns out that cars make a bunch of really bad pollution that causes harmful side effects like death.

This last bit, changing your startup's tack when a better model comes along, is important. And solar roadways needs to do that for a viable product, because their core solution faces a lot of headwinds (yay, sailing puns!) in break-even with their current model.

So, overall, these roads could be an excellent idea. The solar part, their main selling point, is BS because of cost, efficacy, and the need for gas-fired power plants to supplement them. The shutting down most fossil power plants is a lot of nonsense for the same reason. Making the environment better by reducing salt and sand use? Decent. Potentially by making most cars electric? Game-changer, but they are barely looking at that aspect right now. Probably cause they are too busy counting the piles of cash that indiegogo just threw at them (or, more likely, answering the insane number of emails that comes from this sort of campaign).

Hokay, that's my piece. Thanks for reading this long one.

- Jason Munster

Extra stuff!

Some background about Solar Roadways initial funding: They were funded by government SBIR. This stands for Small Business Innovative Research. It's for high-risk, high-reward research. In other words, this was considered high-risk from the start. They got a phase II, which means they did well. It's clear they still have issues and are still high-risk. But I'm glad someone is paying for research and innovation like this, especially because if it pays off, it could result in more jobs and more taxpayer base. That being said, they haven't received more funding or any grants to build this out further. Possibly cause it's a big, crazy idea. Elon Musk can pull off big, crazy ideas, because he is a brilliant manager and has a very strong personality. These guys are going to need some bigger guns on their team if they are going to make something of this project.

Second, Nathan Fillion is a bit of a fool. In touting Solar Roadways, he displays why pop culture heroes shouldn't get involved in matters outside their field of expertise (mainly, looking good in front of a camera, and pretending to be someone who they aren't in front of a camera). His adoration of something he doesn't understand falls deep within the territory of religious fervor. Nerds: just cause one of your heroes likes something doesn't mean it actually is plausible.

One final-final note: I know that this post is 3x longer than my rest. I assure you, it's far shorter than I wanted it to be. I don't believe in two-part posts very often, though. If you have read this far. please leave a comment so I can appreciate you forever 🙂

*Engineers who don't know what numbers to run are a bad investment. For my own company, all business types are skeptical of how much I know (or want to take advantage of me fully) until they find out that I used to be in finance and have a really good idea of the big picture of most things. In short, this company has a lot of potential once they take on broader experts.